Public Policy in the Ecological Model deals with laws, rules, regulations and mandates. This is important because the laws can change to help people with Type 2 Diabetes. Below is information about policy recomendations that are being made for women with Diabetes. It is from the National Center for Chronic Disease Prevention and Health Promotion.Interim Report: | |

Monday, November 15, 2010

Public Policy

Community

The Community level of the Ecological Model includes demographics, economics, geography, culture, transportation, water, financial services, medical system, and environment. These are also things that people with Diabetes encounter every day. Below is a medical service that is doing research to fight Diabetes.

Translating Research Into Action for Diabetes (TRIAD) Fact Sheet, 2009

The Translating Research Into Action for Diabetes (TRIAD) Fact Sheet, 2009

What is TRIAD?

TRIAD is a national, multicenter prospective study that provides useful information about effective treatments and better care for people with diabetes in managed care settings. TRIAD was launched in 1998 to evaluate whether managed care organizations’ structures and strategies affect the processes and outcomes of diabetes care among adults, and to identify the barriers to and facilitators of high-quality care and optimal health outcomes. At that time, there was interest in whether disease management programs would improve diabetes care and outcomes. Numerous TRIAD study publications contribute to an evidence-based body of knowledge that allows managed care organizations and health care policy makers to make informed decisions on ways to improve care for people with diabetes.The TRIAD study group comprises 6 translational research centers (Figure 1) and their 10 health plan partners. When TRIAD began, these health plans contracted with 68 provider groups to deliver primary and specialty care to more than 180,000 adult enrollees aged 18 years and older with diabetes. TRIAD is funded by a cooperative agreement from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK). A list of the investigators at each of the six research centers is available at the TRIAD Web site (www.triadstudy.org

This fact sheet synthesizes 10 years of TRIAD research and analyses and focuses on the following areas:

- How health system factors are associated with processes of care.

- How patient factors determine clinical outcomes, for better or worse, and the effectiveness of diabetes disease management strategies.

Health system factors

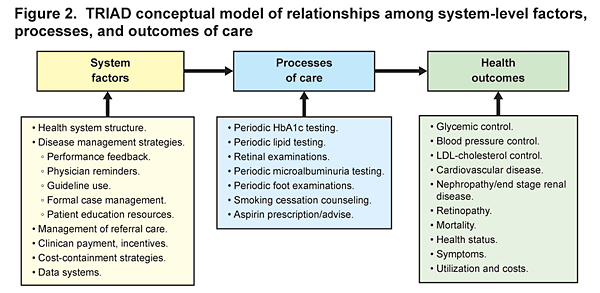

By using Donabedian’s paradigm (Figure 2), TRIAD characterized and examined both managed care structural characteristics and disease management strategies. In Donabedian’s paradigm, system factors are hypothesized to influence patient care processes, which, in turn, influence patient outcomes.

Processes of care

- Improvements in processes of care are not necessarily associated with improvements in intermediate outcomes (e.g., hemoglobin A1c [HbA1c] value, LDL-cholesterol level, systolic blood pressure.

- Greater use of performance feedback measures, physician reminders, and structured care management were strongly associated with better process of care performance. Structured care management included the use and dissemination of clinical guidelines, patient reminders, formal care management and case management by nonphysician providers, and provision of health education resources.

- Accurate clinical data are essential for high-quality chronic disease care. They are needed at both the point of care and in disease registries. However, some health care systems participating in the TRIAD study failed to accurately record simple process measures. One study showed poor concordance between patients’ self-report of recent retinal examinations and medical records of such examinations. The discordance was primarily due to medical records failing to capture patient reported eye examinations.

The effects of cost-shifting

TRIAD found consistent negative effects of cost-shifting to patients. Cost-shifting, whether as copayments or coverage gaps, was associated with reduced recommended medication use and reduced preventive care. Lower income patients appeared to be more sensitive to the effects of cost; however, the effects were present across all income levels.

- Among the 2005 cohort survey respondents, 14% reported using less than the recommended dose of medicine because of cost, and patients with greater out-of-pocket costs were less likely to take the full dose of provider-recommended medicine.

- Compared with those without coverage for selected diabetes services and supplies, participants with full coverage (no out-of-pocket copayments) were more likely to have—

- A retinal exam (78.4% vs. 69.8%).

- Attended a diabetes education session within the prior 12 months (28.8% vs. 18.8%).

- Practiced daily self-monitoring of blood glucose (74.8% vs. 58.6% among insulin users).

-

- Compared with patients in good control for three vascular disease risk factors, those patients not in control for at least two factors were more likely to report that out-of-pocket costs were a barrier to self-management.

Patient factors

TRIAD findings (Figure 3) indicated that health system interventions only modestly affected patient outcomes. Accordingly, the study’s focus shifted to examine the links between (1) patients’ sociodemographic and clinical characteristics and outcomes and (2) outcomes and system factors.

Age

Expressing health risks in terms of more immediate adverse outcomes (e.g., work fatigue and absences, bodily pain, diminished concentration, depressed mood, poor sleep) was more effective in motivating younger than older patients to engage in diabetes self-care than providing information about potential, but not immediate, complications of the disease.- Younger adult patients with diabetes generally received fewer recommended processes of care and were more likely to have persistent lapses in processes of care compared with older adults. Persistent lapses were defined as missing any of five recommended exams over a 3-year period, including HbA1c, cholesterol, microalbuminuria, retinal, and foot.

- Younger patients with diabetes were more likely to have worse intermediate outcomes and less likely to have good risk factor control. Intermediate outcomes were defined as a combined measure of HbA1c, LDL cholesterol, and systolic blood pressure control.

- Younger adult patients were more likely to have had a recent microalbuminuria screening test, even though older patients were at higher risk for chronic kidney disease.

- Among patients 25-44 years of age with less than a high school education, 50% were current smokers compared with only 7% of college-educated persons aged 65 years and older.

- Walking for at least 20 minutes each day was slightly less likely in patients older than 65 than for younger patients (64% vs. 70%), and older patients were less likely to report sustained walking between the second and third TRIAD surveys (63% vs. 71%).

Gender

Although modest, differences were found between men and women in processes and outcomes for cardiovascular disease risk factors (Tables 1 and 2). Compared with men, women in the TRIAD study—- Used less medicine, regardless of their cardiovascular disease (CVD) status.

- Were less likely (among patients without CVD) to be advised to take aspirin or have lipid profile testing.

- Were less likely to control their blood pressure and LDL-cholesterol (among patients in a TRIAD plan with known CVD). However, these women had slightly lower HbA1c levels.

- Had a slightly better HbA1c and LDL-cholesterol control if they had a female physician.

Table 1.

| Processes of care | With CVD | Without CVD | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Women (%) | Men (%) | Women (%) | Men (%) | |

| Aspirin used | 33.2 | 39 | 14 | 16.4 |

| Lipid medications used | 51.5 | 57.6 | 34.8 | 35.9 |

| Aspirin advised in those not taking aspirin | 55.2 | 58.1 | 27 | 32.5 |

| Lipid profile tested in those not using lipid medications | 53.2 | 54.8 | 54.4 | 58.3 |

Table 2.

| Outcomes | Female patients | Male patients | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Female MD (%) | Male MD (%) | Female MD (%) | Male MD (%) | |

| A1c < 8 | 70 | 68 | 66 | 66 |

| LDL-c < 100 | 47 | 46 | 54 | 55 |

| SBP < 130 | 53 | 52 | 60 | 60 |

Race and ethnicity

Whites, African Americans, Latinos, and Asians or Pacific Islanders were well represented in the TRIAD cohort. Although all patients in TRIAD had comparable health coverage, striking disparities in health behaviors and outcomes were found among whites and African Americans. African American patients consistently had poorer control of blood pressure, LDL-cholesterol, and HbA1c.Surprisingly, processes of diabetes care did not differ greatly among the four principal racial or ethnic groups. Compared to whites, African Americans had lower LDL-cholesterol testing (61% vs. 68%) and influenza vaccination rates (59% vs. 68%), but significantly higher foot exam rates (89% vs. 83%). Latino patients had higher dilated eye exam rates (83% vs. 76%) than whites.

However, there were notable racial and ethnic differences in control of all three intermediate outcomes. In 2000, African American patients had the poorest blood pressure control — 45% had blood pressure less than 140/90 mmHg vs. 56% of white patients. For LDL-cholesterol, mean levels were significantly higher for African Americans than white patients (118 vs. 111 mg/dL), but neither Asian/Pacific Islanders nor Latinos differed significantly from whites. All three minority populations had slightly, but significantly higher HbA1c levels than whites.

The TRIAD study findings suggest several possible explanations of the disparities in health behaviors. Compared with white patients with diabetes, African American patients had—

- More sensitivity to out-of-pocket costs.

- Poorer quality of patient-provider relationships.

- Higher prevalence of undiagnosed or untreated depression.

- Fewer resources and greater stress as a result of living in socioeconomically deprived neighborhoods.

Patient-physician interaction

The quality of physician communication and patients’ trust in their physicians were generally associated with better clinical management and outcomes.- Among patients with persistent poor glycemic control on oral agents, those reporting better physician communication and those with fewer misconceptions about insulin were more likely to begin insulin therapy.

- Better patient-reported provider communication (i.e., physicians who listen, explain, show respect, spend time) did not appear to attenuate observed educational disparities in health behaviors (i.e., smoking cessation, increased physical activity, diabetes-related health-seeking activity).

TRIAD key findings, 1998–2008

Implications for health system policies and best practices

Managed care systems should emphasize the development and reporting of care processes known to be closely linked to improved outcomes. Increased system-level attention to monitoring and improving treatment intensification rates may help improve intermediate outcomes. Specific areas for research and possible interventions that may improve the health of people with diabetes include the following:- Redesigning benefits to lessen the cost burden of medicine on patients will ensure more people with diabetes take the prescribed medications.

- Increase cardio-metabolic control and behavioral and medical interventions to treat depression.

- Improve efforts to encourage provider communication and increase patient trust.

- Consider the special needs created by family and work obligations.

- Avoid one size fits all and design programs to eliminate disparate outcomes among populations. For example, greater promotion of mail-order pharmacies could be very useful for patients with problems accessing pharmacies.

- Redesign programs to include sociodemographic and clinical subgroup patient differences in health-related behaviors and control of major cardio-metabolic risk factors.

For other information

For public inquiries and more information about diabetes, please visit the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Web site www.cdc.gov/diabetes/ or call 1-800-CDC-INFO (232-4636).Institutional

The Institutional level of the Ecological Model consists of work, education, recreation, clubs, volunteer groups and faith. These aspects of life are important when dealing with Diabetes because they are the thinks that we take part in every day of our lives. Some benefits that these institutions can have for people are further education about Diabetes, the risk and treatment. Work, recreation and clubs can offer a great opportunity for physical education which can prevent Type 2 Diabetes from occurring and help to manage it better. Below I have posted links to many popular fitness facilities that would help with Type 2 Diabetes. Below it there is also an article from Medline Plus about Diabetes risk and how exercise can help to prevent it.

The Institutional level of the Ecological Model consists of work, education, recreation, clubs, volunteer groups and faith. These aspects of life are important when dealing with Diabetes because they are the thinks that we take part in every day of our lives. Some benefits that these institutions can have for people are further education about Diabetes, the risk and treatment. Work, recreation and clubs can offer a great opportunity for physical education which can prevent Type 2 Diabetes from occurring and help to manage it better. Below I have posted links to many popular fitness facilities that would help with Type 2 Diabetes. Below it there is also an article from Medline Plus about Diabetes risk and how exercise can help to prevent it.Exercise can delay or prevent the onset of Type 2 Diabetes!

Join a fitness club near you!

http://www.carolinemiller.com/tips/nov24-2009.html

"Small Steps, Big Rewards": You Can Prevent Type 2 Diabetes

The good news is, type 2 diabetes can be prevented or treated. By losing a modest amount of weight, getting 30 minutes of exercise five days a week, and making healthy food choices, people at risk for type 2 diabetes can delay or prevent its onset. Those are the basic facts of "Small Steps. Big Rewards: Prevent type 2 Diabetes," created by the National Diabetes Education Program (NDEP). This first-ever, national diabetes prevention campaign spreads this message of hope to the millions of Americans with pre-diabetes (higher than normal blood glucose levels but not yet diabetes)."Fifty four million Americans are at risk for type 2 diabetes."

"Fifty four million Americans are at risk for type 2 diabetes," says Joanne Gallivan, M.S, R.D., NDEP director at the National Institute for Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Disease (NIDDK). "There are steps you can take to prevent it. It boils down to following a healthy lifestyle— not making huge steps, but small steps that can lead to a big reward, such as eating smaller portions and taking the steps instead of the elevator."

The science behind NDEP's campaign is based on the Diabetes Prevention Program (DPP), a landmark study sponsored by the NIH. The study found that people at increased risk for type 2 diabetes can prevent or delay the onset of the disease by losing five to seven percent of their body weight through increased physical activity and a reduced fat, lower calorie diet. That's about a 10 pound weight loss if you weigh 200 pounds.

In the DPP, modest weight loss proved effective in preventing or delaying type 2 diabetes in all high-risk groups. "If you have diabetes in your family, you will want to bring this information to their attention," says Gallivan. "Healthy lifestyles are good for everyone."

For more information: Click here to go to Medline Plus

Interpersonal/ Groups

The Interpersonal level of the Ecological Analysis includes family, friends, co-workers, social groups, relationships and social support. These people in your life can have a great impact on your life with Diabetes or your risk of having Diabetes. For people who have Type 2 Diabetes, the people around you can be there to support you and motivate you to get proper exercise and eat healthy. They can also be there to help with things like testing blood glucose levels and taking insulin shots. I feel that another large role of family in regards to Diabetes is letting everyone know about their disease so that they are prepared. Diabetes is hereditary so family members need to be aware of their higher risk for this disease if other family members currently have it. Below I have attached information from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on how to talk to family members about diseases and risks.

The Interpersonal level of the Ecological Analysis includes family, friends, co-workers, social groups, relationships and social support. These people in your life can have a great impact on your life with Diabetes or your risk of having Diabetes. For people who have Type 2 Diabetes, the people around you can be there to support you and motivate you to get proper exercise and eat healthy. They can also be there to help with things like testing blood glucose levels and taking insulin shots. I feel that another large role of family in regards to Diabetes is letting everyone know about their disease so that they are prepared. Diabetes is hereditary so family members need to be aware of their higher risk for this disease if other family members currently have it. Below I have attached information from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention on how to talk to family members about diseases and risks.

Gather and Share Your Family Health History

If you are concerned about a disease running in your family, talk to your doctor at your next visit. A doctor can evaluate all of the risk factors that may affect your risk of some diseases, including family history, and can recommend you a course of action to reduce that risk.

Thanksgiving is National Family History Day

The US Surgeon General has declared Thanksgiving to be National Family History Day, encouraging Americans to share a meal and their family health history. Family health history information can help health care providers determine which tests and screenings are recommended to help family members know their health risk. This year the Surgeon General updated and improved the My Family Health Portrait tool, which can help individuals collect and organize family history information. Learn more about family health history.

tool, which can help individuals collect and organize family history information. Learn more about family health history.

Family members share genes, behaviors, lifestyles, and environments, which together may influence their risk for developing chronic diseases. Most people have a family health history of common chronic diseases (e.g., cancer, heart disease, or diabetes) and other health conditions (e.g., high blood pressure and high cholesterol). A person with a close relative affected by a chronic disease may have a higher risk of developing that disease than a person who doesn't.

Americans know that family history is important to their health. One survey found that 96 percent of Americans believe that knowing their family history is important. Yet, the same survey found that only one-third of Americans have ever tried to gather and write down their family's health history. Are you ready to collect your family health history but don't know where to start?

Make a list of relatives.

Write down the names of blood relatives you need to include in your history.

- The most important relatives to talk to for your family history are your parents, your brothers and sisters, and your children.

- Next should be grandparents, uncles and aunts, nieces and nephews, and any half-brothers or half-sisters.

- It is also helpful to talk to great uncles and great aunts, as well as cousins.

Prepare your questions.

Among the questions to ask are:

- Do you have any chronic illnesses, such as heart disease, high blood pressure, cholesterol or diabetes?

- Have you had any other serious illnesses, such as cancer or stroke?

- How old were you when you developed these illnesses?

Also ask questions about other relatives, both living and deceased, such as:

- What is our family's ancestry - what country did we come from?

- What illnesses did your late relatives have?

- How old were they when they died?

- What caused their deaths?

To organize the information in your family history you could use a free web-based tool such as My Family Health Portrait .

.

Family history can give you an idea of your risk for common diseases like cancer, heart disease and diabetes, but it is not the only risk factor. If you are concerned about a disease running in your family, talk to your doctor at your next visit. A doctor can evaluate all of the risk factors that may affect your risk of some diseases, including family history, and can recommend you a course of action to reduce that risk.

Intrapersonal

The Intrapersonal level of the Ecological model consists of the personality, knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and skills within the individual. These characteristics will determine whether a person deals with the problem of Diabetes. If a person has no previous knowledge of this disease then they may not know what to expect. Therefore, if that person has no previous knowledge then their attitudes and beliefs about this disease will be very vague. I believe that knowledge is the most important part of the intrapersonal level so below is information from the American Heart Association about Diabetes.

The Intrapersonal level of the Ecological model consists of the personality, knowledge, attitudes, beliefs, and skills within the individual. These characteristics will determine whether a person deals with the problem of Diabetes. If a person has no previous knowledge of this disease then they may not know what to expect. Therefore, if that person has no previous knowledge then their attitudes and beliefs about this disease will be very vague. I believe that knowledge is the most important part of the intrapersonal level so below is information from the American Heart Association about Diabetes.About Diabetes

"Diabetes mellitus," more commonly referred to as "diabetes," is a condition that causes blood sugar to rise to dangerous levels: a fasting blood glucose of 126 milligrams per deciliter (mg/dL) or more.

How Diabetes Develops

1. Right away, the body's cells may be starved for energy.

2. Over time, high blood glucose levels may damage the eyes, kidneys, nerves or heart.

Types of Diabetes

There are two main types of diabetes: type 1 diabetes and type 2 diabetes. Both types may be inherited in genes, so a family history of diabetes can significantly increase a person's risk of developing the condition.

Type 2 diabetes is the most common form of diabetes. Historically, type 2 diabetes has been diagnosed primarily in middle-aged adults. Today, however, adolescents and young adults are developing type 2 diabetes at an alarming rate. This correlates with the increasing incidence of obesity and physical inactivity in this population, both of which are risk factors for type 2 diabetes.

This type of diabetes can occur under two different circumstances:

This type of diabetes can occur under two different circumstances:

- The pancreas doesn't make enough insulin, or

- The body develops "insulin resistance" and can't make efficient use of the insulin it makes

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)